Which birds are farmed for their eggs

For the most part, chickens and ducks are the only birds that are commercially farmed for their eggs. Chickens probably account for around 90 or 95% of all eggs produced and eaten around the world. The largest market for duck eggs is the far east.

Any other poultry eggs are specialist items only found in delicatessens or similar stores. If you want to eat eggs other than chickens or ducks eggs you will probably either need to know someone who keeps those birds or get them yourself.

Luckily over the years I have kept many types of poultry and tried the eggs.

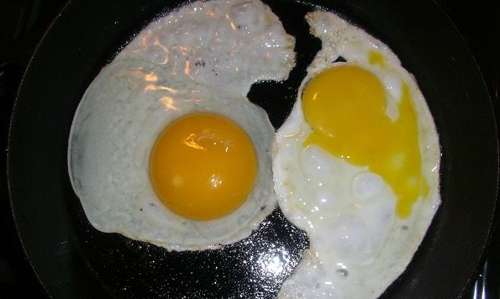

Below: A size comparison between a chicken and a duck egg.

You can eat the eggs from just about any bird but with nearly all of them it is just not a realistic proposition.

You must only eat eggs from farmed poultry - collecting wild birds eggs is illegal just about everywhere!

Please also bear in mind that poultry differs from one continent to another and my experiences may not be the same as yours. The birds diet also effects the egg.

Do eggs from other types of poultry taste the same?

Similar but not the same. All eggs are different. Eggs from a guinea fowl for example taste similar to a chickens egg but the ratio of yolk to white is different in eggs from different species of bird.

In my mind the yolks from duck eggs have a silky texture and are my personal favourite.

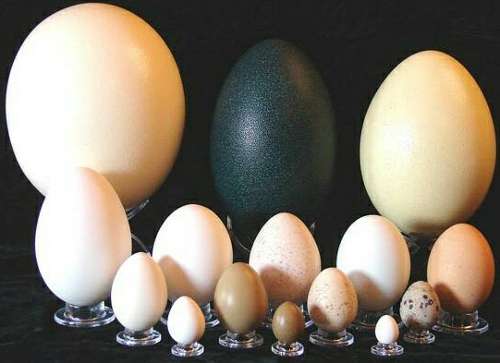

Below: Eggs from 15 types of poultry. From Ostrich to Quail.

Eggs also taste different due to the diet and feed of the bird. Not all chickens egg taste the same either. A free range egg from a backyard flock will taste much better than an intensive farm reared egg.

Which birds are considered domestic poultry?

List of types of poultry that are farmed:

- Chickens.

- Ducks and Muscovy ducks.

- Quail.

- Guinea fowl.

- Geese.

- Turkeys.

- Ostrich

- Partridge.

- Pheasant.

- Emu.

- Rhea.

What other eggs do we eat?

Most commonly eaten eggs are Chicken, Duck, Guinea fowl, Quail, Goose, Ostrich and Turkey. There is a rise in the production of alternative types of eggs.

I keep most types of small domestic poultry. I have chickens, ducks including Muscovies, Guinea fowl, Geese, Quail and Turkeys and eaten eggs from all of them.

In my local store I can buy chicken, duck and guinea fowl eggs as well as coloured eggs from selected rare breeds.

There is a restaurant in London where you can get a full English breakfast served with an ostrich egg. It is eye wateringly expensive though.

Why aren't some types of poultry farmed for their eggs?

Most other types of poultry are not as easy to keep or as productive when it comes to producing eggs and meat as chickens. Chickens are easy to keep in flocks and have a short time before they become productive.

Most poultry is dual purpose meaning that historically they were kept in small number for their meat as well as their eggs and feathers.

This makes eggs from anything other than chickens very expensive in comparison. In my local store I can buy 15 chicken eggs for £2 and 6 duck eggs for £3.

Money is a big reason that most other types of birds are not farmed intensively like chickens. A turkey might only lay 50 to 80 eggs a year and the market is for birds for celebration meals like thanksgiving and Christmas. So it does not make sound business sense to sell the eggs to end consumers.

Another reason is that taking eggs form the nests of some species will scare them off the nest and they won't lay anymore. Lack of domestication is a big problem. This is pronounced in pheasants where they have to be allowed to lay a clutch before you collect the eggs.

Chickens:

Chickens are kept for their eggs because they are social creatures that are easy to keep in large flocks. They are easy to produce in large numbers and grow quickly to maturity.

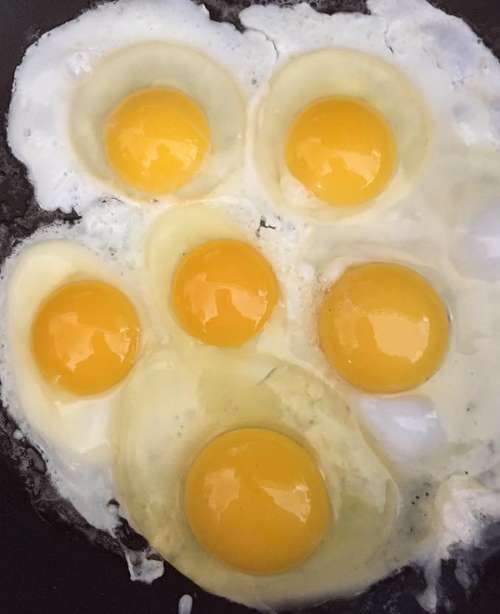

Below: A selection of eggs from my chickens of all shapes and sizes sunny side up in the pan.

Much has been invested in producing hybrids that lay large numbers of eggs from thrifty birds and most consumers are happy with the product.

Some breeds produce nicer eggs and a full range of colours and sizes is produced.

Guinea fowl:

I keep Guinea fowl but they are not suitable for every keeper. They have really thick shells.

There are many disadvantages to keeping guinea fowl just for their eggs. They are noisy birds that fly well and do not lay anything like as many eggs as chickens do. The eggs are also smaller than chicken egg by around a third.

Below: a bowl of guinea fowl eggs.

On the plus side, Guinea fowl eggs are amazing to eat, the yolks are golden and large for the size of the egg. They are also thrifty birds if allowed to free range as they graze well. Guinea fowl are also good to eat.

My favourite way to eat guinea eggs is poached.

Ducks:

Duck Eggs are really nice. They are bigger than chicken eggs by about 10 to 30% depending on the breed and have bigger yolks. The yolks also tend to be much more deeply coloured and richer in flavour because of the diet of ducks.

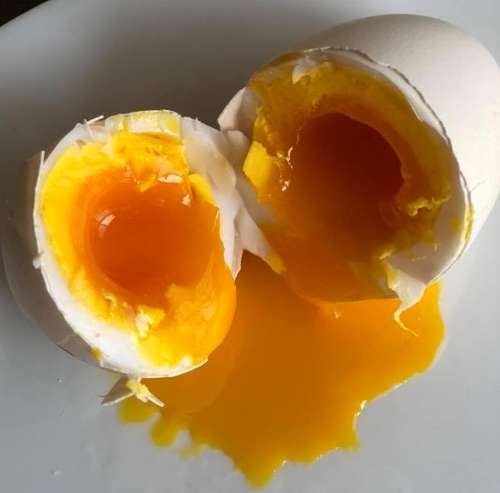

Below: A soft boiled duck egg with a runny yolk.

Ducks can be quite productive, they have been subject to selective breeding for at least 200 years so it's not uncommon for ducks to produce 180 eggs a year. They are more seasonal layers and lay fewer eggs than hens and take much longer to fist eggs, often a full year. This makes the birds more expensive to buy.

Below: A size comparison between two duck and two chicken eggs.

I really like the eggs from my Indian runners and they are my go to choice for both my breakfast and baking.

For me when I eat duck eggs they have to be Sunny side up, fried in a little butter.

Duck eggs are difficult to find, and can be a great alternative if you have allergies to chicken eggs. Duck eggs contain more vitamin A, B12, D, and Omega-3 then chicken eggs.

Turkeys:

Traditionally kept for meat purposes you can eat turkey eggs. The eggs are much bigger but tasty. The trouble is that turkeys only lay 30 to 50 eggs a year and they are almost always in spring and early summer.

Below: Turkey eggs.

I don't think any of my turkeys has laid after July even if I take all their eggs away and don't let them raise a clutch of poults.

I only got to eat three turkey this year and poached them all.

Geese:

The goose is well known for it's egg even though it has traditionally been a meat bird. Modern commercial types can produce 60 to 80 eggs a year. The birds take a long time to mature and only lay in their second year.

Below: Two goose eggs in the hand to show size.

I always eat a few goose eggs every year and have a few customers that wait patiently for and pay handsomely for for goose eggs. Geese are more protective of their nests so some care is required.

Below: A Goose egg in the pan with a hand for comparison.

Large eggs like the goose benefit from being scrambled as they take a long time to cook otherwise and the yolks may be cold in the middle if you get it wrong.

Ostrich:

I grew up in Africa and had many opportunities to eat Ostrich eggs. They are huge and one will feed two or more people. They do come up for sale and I have seen them in stores.

Below: An Ostrich egg in a mixing bowl.

The flavour of the egg is unremarkable and not dissimilar from the chickens' egg. The yolks are more golden and richer than a chickens egg. They are more rubbery in texture and the texture is something you will notice if you eat Ostrich eggs. An ostrich egg taste as somewhat similar to hen’s eggs. As compared to other eggs, ostrich eggs taste more buttery and richer. However, the taste can be slightly more intense; some even say gamy.

You also need a hammer or the back of a sharp knife to crack an Ostrich egg, the shells are very strong.

Here in England we have quite a few ostrich farms but the bird is kept almost exclusively for meat and it's decorative feathers.

Below: A restaurant in London serves an full English breakfast with an Ostrich egg.

When I lived in Africa we used to bake Ostrich eggs in the hot sand underneath a campfire. I have only had one in recent years and that was part of a fried breakfast. It is a shared breakfast as the egg is roughly equivalent to 24 chicken eggs.

The season is quite short. My favourite way to eat them is scrambled with friends.

They are often blown out, ie emptied with small hole at either end so as the shell can be preserved.

Emu:

They are a beautiful dark green in colour and can weigh up to 700g or the equivalent of 10 chicken eggs and the taste is somewhat different to a normal egg and seems to have more yolk than white.

Below: Emu eggs are a magnificent green colour.

Below: Cooking with an Emu egg.

Its a different taste to a normal egg and seems to have more yolk than white.

Rhea:

The Rheas' egg is straw coloured although the shade varies during the season and from bird to bird. A large one weighs about 2lb and is roughly the equivalent of 10 hens' eggs.

Below: A Rhea egg.

Below: Here they are in the pan cooking.

Eating Rhea egg is hard work, the shells are especially thick and the flavour is the most unusual of any birds egg I have eaten. Rhea eggs are stronger in taste and not for everybody.

Grouse:

Grouse are game birds kept for their meat and often bred only to hunt.

Below: Some Grouse eggs in the incubator.

As a result the eggs are never eaten.

Bantams:

Bantam eggs are nice. They are better than the standard chicken egg you buy in the store. Bantams lay fewer eggs and the quality tends to be better especially in small backyard flocks where the bird are allowed on pasture. The reason you don't seem them in your local store is their size.

Below: Eggs from my free range bantams.

Essentially small birds are difficult to make money and profit out of so suppliers do not seem to bother.

My favourite way of eating bantam or true bantam eggs is baked with veg or meat pieces in a dish like baked egg huevos.

Quail:

The quails egg is a bit richer in texture and colour and have a larger yolk to white ratio than chicken eggs do.

Below: Quails eggs.

When cooking or baking with quail eggs, 3-6 quail eggs equals 1 chicken egg. With our eggs, we typically use about four.

Quails eggs have been popular in restaurants for many years. They are small, making them hard work but tasty.

Below: Quails eggs being cooked.

My favourite way to eat quails eggs is soft boiled (just cooked, 2min 15 sec) and sliced into salad.

Pheasant:

Where I live in the North of England, pheasants are mostly raised for shooting as game birds and the eggs are rarely eaten.

Below: Eggs from Pheasants for sale. If you know where to get them.

I have kept pheasants, purely by accident. I had one join my chickens and start using the coop floor to lay eggs, which I incubated and hatched under a Silkie cross. I got 4 females that laid 50 eggs a year or so.

They were always flighty and never settled down. The eggs are around 80% of the size of a chicken egg and the taste compares well to that of the duck egg.

Partridge:

Partridges are classically a meat bird but you can eat the eggs.

Below: Partridge egg marked for incubation.

The meat is much more valuable then the eggs so they are almost never eaten.

Peafowl:

Peafowl are mostly ornamental although they have graced the dining tables of the rich in history. Peafowl usually only produce one clutch of 12 to 16 eggs although if you take the eggs away they may produce a second clutch month or so later.

Below: A comparison of a peafowl and chickens egg.

Below: Here is a cooking peafowl egg. Notice the large yolk size.

They are also difficult to keep and have a habit of just flying away when they feel like it.

I did once, in one of the most expensive dining experiences I have ever had, have 2 poached Peahen eggs for breakfast. They are comparable to turkey eggs in size and taste and were nice but nothing special and certainly not worth the £10 each I paid for them as far as egg eating goes.

Are eggs from other types of poultry healthier for you?

Eggs from free range poultry will be healthier for you and it stands to reason that if the bird is producing less eggs they will have more nutrients.

It's a little difficult to describe but having eaten a lot of my own eggs and having store bought I would say that home produced are much fresher, tastier and have higher levels of nutrients.

Duck eggs are richer than chickens eggs and are known to have around 3 times the level of some nutrients like omega -3 and b vitamins.

I expect the war of words over how healthy eggs are for humans will rage on for years.

My 2 cents worth is that humans have been raiding birds nests and eating eggs for tens if not hundreds of thousands of years.

Ways to cook eggs:

There are five basic methods for cooking eggs. The basic principle of egg cooking is to use a medium to low temperature and time carefully.

When eggs are cooked at too high a temperature or for too long at a low temperature, whites shrink and become tough and rubbery; yolks become tough and their surface may turn gray-green.

Eggs, other than hard-cooked, should be cooked until the white is completely coagulated and the yolks begin to thicken. The five methods are:

Baked (also known as shirred):

For each serving; break and slip two eggs into a greased ramekin, shallow baking dish or 10-ounce custard cup. Spoon one tablespoon of half and half, light cream, or milk over eggs. Bake in pre-heated oven at 325°F until whites are completely set and yolks begin to thicken but are not hard, about 12-18 minutes, depending on number of servings being baked.

Cooked in the Shell (eggs in their shells cooked in water):

Place eggs in single layer in a saucepan and add enough water to come at least one inch above eggs. Cover and quickly bring just to boiling. Turn off heat. If necessary, remove the pan from the burner to prevent further boiling. Let the eggs stand, covered, in the hot water, the proper amount of time.

- Hard-cooked:

Let stand in hot water about 15 minutes for Large eggs. (Adjust the time up or down by about three minutes for each size larger or smaller). To help prevent a dark surface on the yolks, immediately run cold water over the eggs or place them in ice water until completely cooled. (Unfortunately, it is almost impossible to cook eggs to this state at altitudes about 10,000 feet). Note: The term "boiled eggs" is a misnomer for eggs cooked in the shell. Although hard- and soft-boiled eggs are terms often used in conversation, the proper term is hard-cooked or soft-cooked eggs. Eggs should NOT be boiled because high temperatures make them tough and rubbery. - Soft-cooked:

Let stand in hot water about four to five minutes, depending on desired final texture. Immediately run cold water over the eggs or place them in ice water until cool enough to handle. To serve out of the shell, break the shell through the middle with a knife. With a teaspoon, scoop the egg out of each shell half into a serving dish.

Fried (cooked in a small amount of fat in a pan):

In a seven or eight-inch omelette pan or skillet over medium-high heat, heat one to two tablespoons butter or margarine until just hot enough to sizzle a drop of water. Break and slip two eggs into the pan. Immediately reduce the heat to low. Cook slowly until whites are completely set and yolks begin to thicken but are not hard, covering with lid, spooning butter over the eggs to baste them, or turning the eggs to cook both sides.

Poached (eggs cooked out of the shell in hot water, milk, broth or other liquid):

In a saucepan or deep omelette pan, bring one to three inches of water or milk to boiling. Reduce the heat to keep the water gently simmering. Break cold eggs, one at a time, into a custard cup or saucer or break several into a bowl. Holding the dish close to the water's surface, slip the eggs, one by one, into the water. Cook until the whites are completely set and the yolks begin to thicken but are not hard, about three to five minutes. With a slotted spoon, lift out the eggs. Drain them in a spoon or on paper towels.

Scrambled (yolks and whites beaten together before cooking in a greased pan):

For each serving, beat together two eggs, two tablespoons milk and salt and pepper to taste until blended. In a seven to eight-inch omelette pan or skillet over medium heat, heat two teaspoons butter or margarine until just hot enough to sizzle a drop of water. Pour in the egg mixture. As the mixture begins to set, gently draw an inverted pancake turner completely across the bottom and sides of the pan, forming large soft curds. Continue until the eggs are thickened and no visible liquid egg remains. Do not stir constantly.